Intro

\(PM_{2.5}\)

Since the health effects of particulate matter (PM) pronounced by the groundbreaking six cities study whose pioneer work linked air pollution to elevated mortality rate1, a large body of literature has found exposure to particulate matter associated to a wide range of deleterious health outcomes , such as asthma , cardiovascular disease, lung cancer, and cognitive decline . Fine particulate matter, defined as particulate matters with aerodynamic diameter less than 2.5 μm, was the foci of most of these studies, since they travel deeper into alveolus and impose higher health risk. A recent in vitro study has also found that low dose of \(PM_{2.5}\) exposure for only 24 hours can induce acute oxidative stress, inflammation and pulmonary impairment in healthy mice2. Therefore, highly resolved-spatial and temporal evaluation of ambient PM levels becomes particularly relevant in furthering scientific basis for next-step air pollution regulation.

AOD

Aerosol optical depth (AOD) measures light extinction by aerosol in the atmospheric column above the earth’s surface. It is measured by NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) daily globally. Thanks to its wide spatial availability, AOD compliments the sparsity of ground level PM monitors readings in works using spatial interpolation to better profile individual’s exposure level.

Other factors

PM-AOD models suffer from two limitations; first, factors correlated to both AOD and ambient PM concentration, such as planetary boundary height and meteorological oscillation, may introduce high instability to the model; second, the association between AOD and PM has tendency to fluctuate on a daily basis, predominated by certain temporal and spatial correlation patterns. Both issues call for more sophisticated model calibration than simple AOD and \(PM_{2.5}\) empirical regressions. Some investigations tackled the first issue by controlling for local meteorological information3, land use information or both; incorporating whether the aerosol is confined to the surface planetary boundary layer (PBL) or aloft can also engender a better agreement with surface PM level ; those findings suggested endogenizing those information in the predictive model, although a reliable ex ante model specification could not be provided. For the second issue, sophisticated statistical methods such as linear mixed effect model and neural network are employed to deliver a more stable parameter estimation, advocating data-driven model selection method in this category of predictive models.

The aim of this study is to calibrate an AOD-land use-\(PM_{2.5}\) model using a data-driven model selection to interpolate \(PM_{2.5}\) concentrations spatially and temporally in Greater London area.

Data

Study area

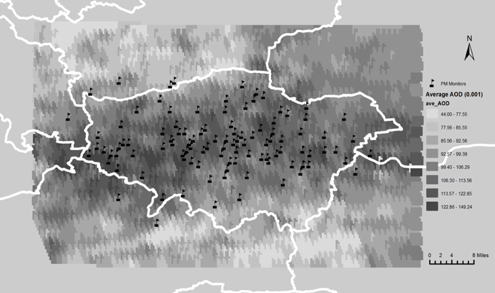

Our study is located in the Greater London Area, a rectangular region ranging from -0.561° to 0.372° in longitude and 51.217° N to 51.798° N in latitude. The study region comprised a mixture of urban and rural areas and a wide variation of population density, which ranges from the most populated borough of Islington (14,517 people/\(km^2\)) in the greater London area to the least populated neighborhood Sevenoaks in county of Kent (317 people/ \(km^2\)).

Figure 1. the Greater London Area

AOD

AOD data can be downloaded from NASA MODIS, although those data is very chunky and sparse, requiring significant amount of storage and computational power to process (Thanks to my colleague Qian, Di for the initial acquisition). NASA developed an algorithms (multi-angle implementation of atmospheric correction algorithm4) to deduce AOD from MODIS remote-sensing data, which have a theoretical precision of ±0.05τ . NASA provides AOD readings at a precision of 1 km × 1 km grid cells. The study region was covered by an orthogonal array that consisted of 22,878 such grid cells.

Meteorological data and air pollution data

Spatial-Temporal Exposure Assessment Methods (STEAM) project led by King’s College, London provided \(PM_{2.5}\) daily concentration at 29 ground-level monitors, as well as meteorological factors comprising of barometric pressure (BP), temperature (TMP), cloudiness (CLD), dew point temperature (DEWA), wind speed (WDSP), wind direction (WDIR) and planetary boundary layer height (PBLH). (These are proprietary data.) In preparation, we spatially joined each day’s meteorological data to AOD readings, using an algorithm that allowed for adjacency allocation varying daily. Number of households and population density was extracted from the 2011 census and merged to the AOD grid cells.

Figure 2. Average AOD readings from 2004 to 2014 in the study area and locations of \(PM_{2.5}\) monitors.

Model training

The $ex ante$ model

\(PM_{2.5_{ij}}=β_0+b_{1j}+(β_{1}+b_{2j})×AOD_{ij}+β_3×((AOD_{ij},Time_j,BP_{ij},TMP_{ij},CLD_{ij},DWEA_{ij},WDSP,PBLH_j))^2 +β_4×WDIR_{ij}+ϵ_{ij} , (b_{1j},b_{2j} )~ N(0,Σ)\)

\(AOD_{ij}\) notifies AOD readings on day j at site i. \(b_1\) and \(b_2\) stand for the random intercept and random slope of AOD through time.

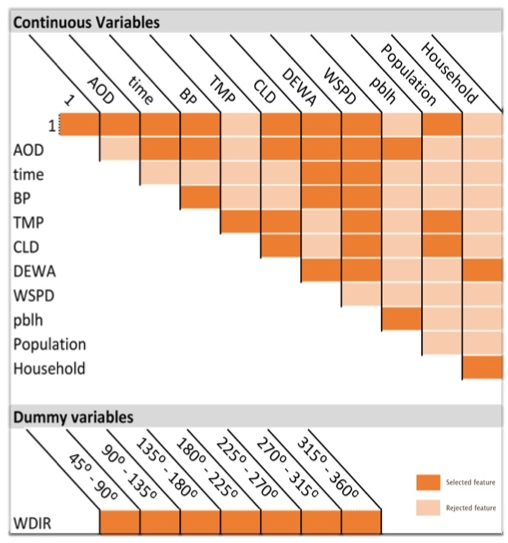

LASSO

The ex ante model allows for many interaction terms in the \(β_3\) term, which may result in overfitting. For model selection, we use east absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) to identiy the optimal predition model. At the optimal penalty \(\lambda\), model selection results are demonstrated as follow:

Figure 3. Demonstration of final model selection produced by LASSO. Final model has degrees of freedom of 39.

We then used the model specification generated from LASSO to predict the spatial and temporal distribution of \(PM_{2.5}\) in Greater London area. All model training and prediction was done using R version 3.3.0 (2016-05-03).

Results

Temporal cross-validation

Mean and standard deviation for 10-fold cross validation \(R^2\), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), mean absolute error (MAE)

| CV_R2 | SD(CV_R2) | MAPE | SD(MAPE) | MAE | SD(MAE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 - 2014 | 0.844 | 0.002 | 0.238 | 0.006 | 3.560 | 0.023 |

| 2004 | 0.775 | 0.007 | 0.248 | 0.008 | 3.008 | 0.061 |

| 2005 | 0.819 | 0.007 | 0.245 | 0.005 | 3.126 | 0.064 |

| 2006 | 0.801 | 0.004 | 0.205 | 0.101 | 2.951 | 0.059 |

| 2007 | 0.794 | 0.009 | 0.244 | 0.029 | 3.476 | 0.181 |

| 2008 | 0.863 | 0.003 | 0.256 | 0.015 | 2.942 | 0.050 |

| 2009 | 0.811 | 0.003 | 0.234 | 0.006 | 3.531 | 0.044 |

| 2010 | 0.717 | 0.012 | 0.260 | 0.046 | 3.133 | 0.102 |

| 2011 | 0.854 | 0.002 | 0.224 | 0.009 | 4.506 | 0.046 |

| 2012 | 0.839 | 0.006 | 0.273 | 0.016 | 4.416 | 0.102 |

| 2013 | 0.806 | 0.005 | 0.229 | 0.009 | 4.288 | 0.039 |

| 2014 | 0.811 | 0.031 | 0.248 | 0.094 | 2.191 | 0.119 |

Spatial cross-validation

Mean and standard deviation for spatial 10-fold cross validation \(R^2\), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), mean absolute error (MAE), categorized by quartiles of performances of the 120 \(PM_{2.5}\) monitors

| CV_R2 | SD(CV_R2) | MAPE | SD(MAPE) | MAE | SD(MAE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 0.919 | 0.007 | 0.241 | 0.000 | 3.508 | 0.103 |

| 25% | 0.944 | 0.066 | 0.138 | 0.022 | 2.082 | 0.437 |

| 25% - 50% | 0.933 | 0.041 | 0.198 | 0.014 | 2.873 | 0.652 |

| 50% - 75% | 0.924 | 0.051 | 0.245 | 0.018 | 3.645 | 0.657 |

| 75%-100% | 0.876 | 0.127 | 0.385 | 0.090 | 5.433 | 1.609 |

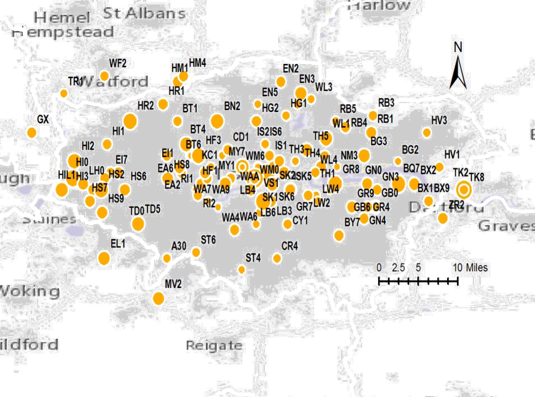

Plot the MAE of each monitoring sites in the study area to investigate into the spatial pattern of error distribution. Moran’s I test based on cross-validation R2, MAPE, MAE reported P-values of 0.36,0.43 and 0.53, indicating no detectable spatial autocorrelation. Therefore, although \(PM_{2.5}\) monitors were spatially centered, the accuracy of didn’t significantly change moving outwards, indicating that the predictive power of our model was stable across space.

Figure 4. Spatial distribution of mean absolute error.

Figure 4. Spatial distribution of mean absolute error.

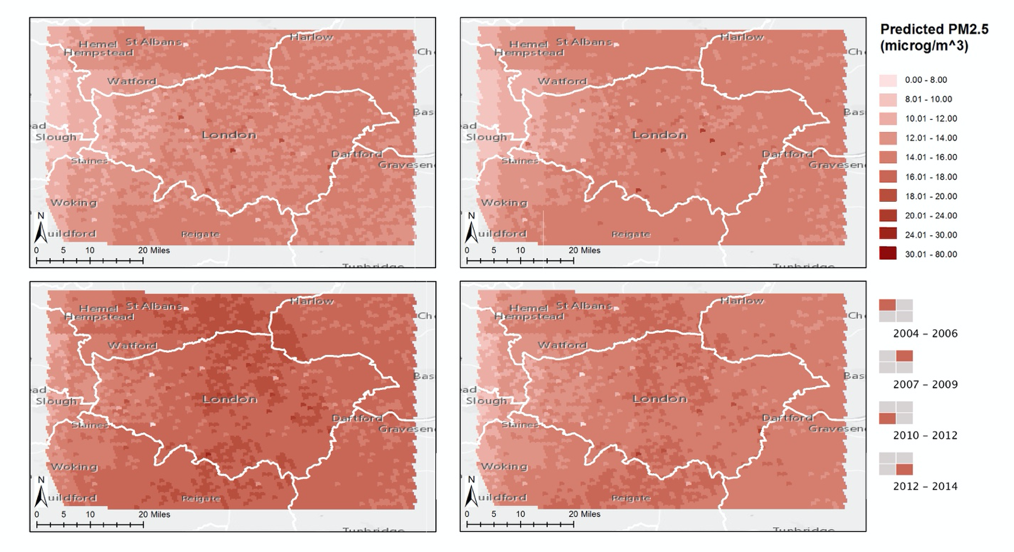

Prediction

Finally we plot the predictions of particular spatial / temporal \(PM_{2.5}\) concentration. Expectedly, the more built-up north region showed higher concentration of \(PM_{2.5}\), particularly in 2010 – 2012 period. Spikes of \(PM_{2.5}\) predictions tend to appear in the center of the city, except for period 2010 – 2012, when there was an abnormal meteorological phase.

Figure 5. Spatial distribution of total \(PM_{2.5}\) in Greater London from 2004 to 2014.

Discussion

There are a few limitations of our study. First, we failed to verify the predictive power based on temporally randomized cross-validation. It is likely that the significant seasonal change of cloudiness and fogginess in the study region rendered the availability and quality of AOD measures excessively variable across time, which would compromise the model’s predictive power temporally; therefore, our model is not suitable for prediction of \(PM_{2.5}\) concentrations at a specific time point. Second, only using population density and household’s numbers forbad detections of more granular \(PM_{2.5}\) variabilities across space. Features like road density and industry location should be included for further studies when such granular \(PM_{2.5}\) predictions are desired. With the rapidly increasing spatial and temporal resolution of satellite and ground-level monitoring, further studies should be expected to yield more accurate exposure assessment that better facilitates spatially specific and long time-span epidemiological studies.

Testting

-

Dockery, Douglas W., et al. “An association between air pollution and mortality in six US cities.” New England journal of medicine 329.24 (1993): 1753-1759. ↩

-

Riva, D. R., et al. “Low dose of fine particulate matter (PM2. 5) can induce acute oxidative stress, inflammation and pulmonary impairment in healthy mice.” Inhalation toxicology 23.5 (2011): 257-267. ↩

-

Schaap, M., et al. “Exploring the relation between aerosol optical depth and PM 2.5 at Cabauw, the Netherlands.” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 9.3 (2009): 909-925. ↩

-

Lyapustin, A., et al. “Multiangle implementation of atmospheric correction (MAIAC): 2. Aerosol algorithm.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 116.D3 (2011). ↩